Autism is a neurotype that is part of natural human neurodiversity. Autistic people are diverse, too; we are of every gender, race, culture, sexual orientation, religion, etc. in the world, as well as every age, and are unique in all the ways people can be. However, we have in common a group of differences from neurotypical people in areas including socializing, communication, motor skills, sensory perception, flexibility of thought, executive function, and more. These differences can be challenging, wonderful, or both — or just our normal.

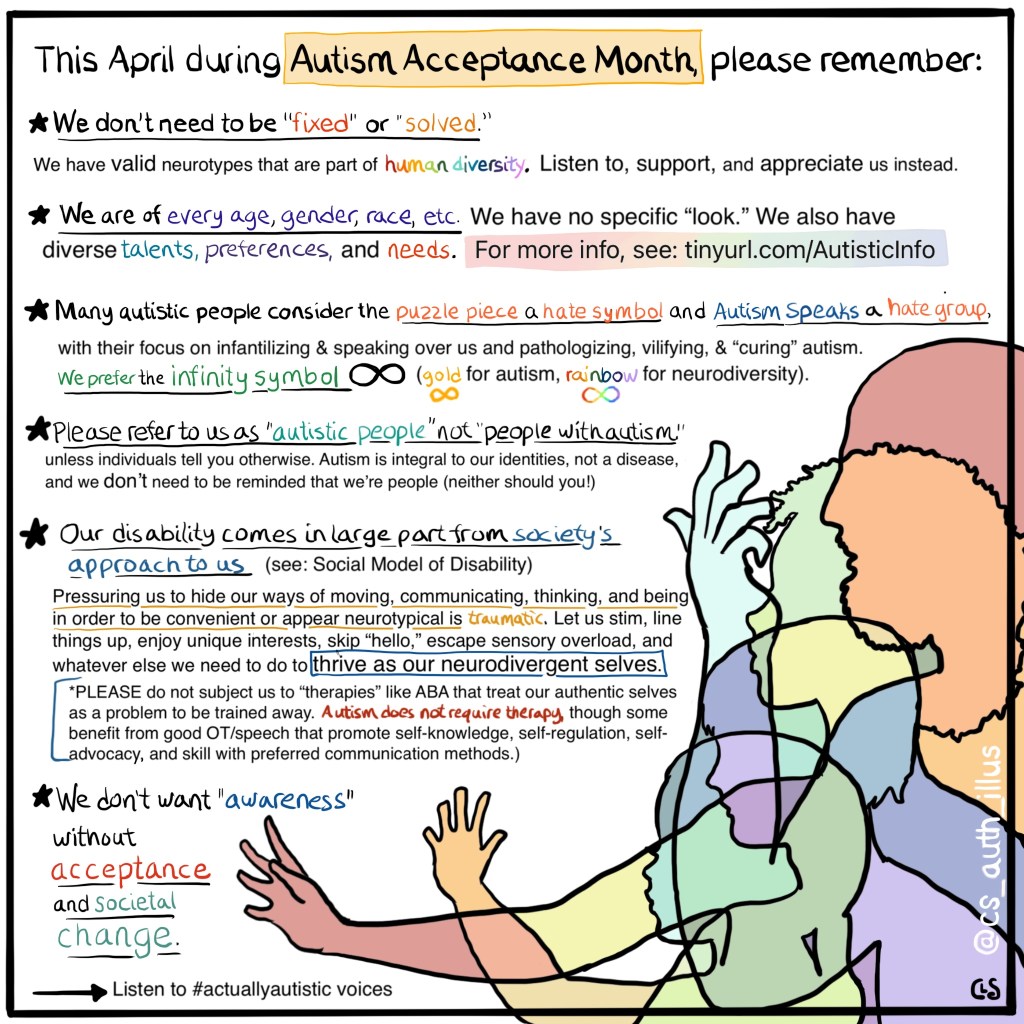

I began Autism Acceptance Month this year by making the infographic below in the hopes of helping our autistic voices to be heard during a time when lots of misinformation is shared about us:

The infographic gives an overview of facts and common preferences of the autistic community, but doesn’t explain in depth what it means to be autistic, so in honor of Autism Acceptance Month, I’m sharing more here — and will continue to add information and resources as I become aware of them.

What does it mean to be autistic?

From my experience and research, some common traits of autistic people are as follows. (Because Autism has many possible components and everyone has a different mix of traits, every autistic person is not just unique as a human, but unique in how we are autistic, so these won’t apply to every autistic person. Also, while some of these traits are disabling, many of these traits which may seem like a problem from a neurotypical perspective are in fact just not typical. It’s ok to let us be who we are and support/accommodate us as necessary for our happiness, fulfillment, and wellbeing.)

- Communication differences:

- Difficulty with social pragmatics of communication, including slang, conversation flow, greetings, etc. We often speak formally and may use informal language in unexpected ways if we do use it.

- Missing subtext, sarcasm, hidden meanings, etc.; literal use of language. We generally interpret what others say to us as being sincere — just as we are, in general, sincere in our communication. We are also often unaware of subtext such as implied requests within a statement.

- Eye contact can feel very intense to us, and its norms are not intuitive. We may “mask” with eye contact that seems not-quite-right to neurotypical people, either because we look away frequently or not enough. We often listen better if we are not expected to look at someone’s eyes or even face them. We may listen best if we are also fiddling with something, drawing a picture, or moving, etc.

- Auditory processing delays, which can lead to challenges in following a conversation, extricating words meant for us from other sounds around us (this difficulty with differentiating background noise from what we need to listen to can be part of what leads to sensory overload in loud areas), preferring to have same-language subtitles on while watching television, preferring to have written materials instead of lectures, preferring visual instructions, etc.

- We may have unusual rhythms or volume or tone to our speech, such as speaking in a monotone, speaking loudly in a close space, or speaking quietly from far away yet expecting to be heard. We may also struggle to recognize appropriate occasions for formal vs informal speech.

- Echolalia. Many of us repeat words/phrases from ourselves or others, either frequently or infrequently.

- Expressive/receptive language challenges, or advancements such as hyperlexia. We have, as a group, a broad range of skills and challenges in this area. We may also have a range as individuals, perhaps being, for example, an unusually capable reader/writer with selective mutism, etc.

- Some autistic people do not speak with mouth words (or do not often speak, or do not speak until adulthood), but can understand and can communicate in alternative ways including sign language, AAC devices, typing/writing, etc. We should presume competence and stay away from using “age equivalents” to infantilize nonspeaking autistic people.

- Difficulty navigating neurotypical social rules and cues

- This is not the same as being an introvert; autistic people are often very motivated to seek out social connection, but we may do so in atypical ways and struggle as a result. (We might, of course, be introverts too, just as anyone else might).

- We generally find small talk to be very stressful since it is all about meeting unwritten social expectations and not about actually saying things.

- We may frequently forget to say hello, goodbye, thank you, etc., but rather jump straight into a topic. Leaving these out does not mean we don’t care — we just don’t intuit social and communication norms.

- We may “script” our interactions, practicing and even writing down wording, both for specific interactions (especially phone calls!) and to memorize long-term so we’re prepared with known statements/responses for many kinds of situations.

- We may find unscripted conversation to be difficult to navigate and very anxiety provoking, including unexpected phone calls (we may send them to voice-mail, then prepare ourselves emotionally and verbally to return the call) or social circumstances that have their own unwritten rules, such as restaurants, coffee shops, hair salons, drive-thru windows, shops/services, etc.

- Autistic people tend to respond to others’ personal sharing with our own sharing instead of making statements like “That must’ve been scary/exciting/etc.” We may be misinterpreted as egocentric because of this, but it is in fact just a different way of showing connectedness. We may also not understand when it’s appropriate to share personal experiences versus staying superficial, so we over share.

- Another big social difference is manipulation and deceit. For many autistic people, this is not intuitive to us — either in terms of lying ourselves or understanding when somebody else is not being truthful. As a result, we may be perceived as “gullible,” not know when someone is kidding unless they are explicit, and be upset by tricks/pranks. We may also be honest to the point of hurting others’ feelings without intending to do so.

- Many of us crave connection, but feel like anthropologists or aliens, studying peers and trying and often failing to correctly mimic them — or to fit in as we are.

- As children, we may feel like adults; as adults, we may feel like children, both from confusion about social rules and the fact that we often keep childhood interests life-long (in my opinion, it’s wonderful to not leave childhood’s magic behind even as we take on adult roles and responsibilities)

- We may find fashion and other social trends to be confusing, mysterious, or not a priority.

- We may have high levels of social anxiety and may also perseverate/ruminate on perceived social and other failures, sometimes for years and in specific detail.

- Sensory issues

- Most of us have heightened sensitivity to some or all of the following: light, sound, smells, unexpected physical contact, materials/textures in clothing (as well as makeup/nail polish/lotion, etc.), texture or other characteristics of food and drink, etc.

- This is not about being “picky.” We can feel true distress and pain from sensory input and can enter a state of sensory overload from these inputs (and others) and reach overwhelm, meltdown or shutdown, and sometimes dissociation. These might look like a tantrum or “ignoring” or other things, but they aren’t; these responses to overstimulation are not under our control.

- Regulation differences in the vestibular system (ie balance/orientation), proprioceptive system (ie awareness of place in space), and in interoception (ie awareness of bodily needs like hunger, thirst, temperature, pain, bathroom needs).

- Many people are first diagnosed with something called “sensory processing disorder” before or alongside an Autism diagnosis.

- Some autistic people are “sensory seeking” – looking for more input from the world to feel balanced and at home in the body – while others are “sensory avoidant,” seeking refuge from sensory input. More often, though, we have a mix of both.

- Related to sensory issues is “stimming,” or self-stimulatory behavior.

- These “stims” look different for everyone but there are many common types, including visual, auditory, tactile, physical, even olfactory.

- Stimming is a very important way for autistic people to self-regulate and can look lots of different ways:

- we may do the well-known hand-flapping, rocking, or humming,

- but also many other things, like: spinning/watching things spin, jumping/putting pressure on joints, clenching muscles, biting fingers/inside of cheeks/etc., flicking or pressing fingers/toes, watching our hands stim, hair-twirling, eye blinking, rubbing or squeezing something, using sand/water/other sensory-calming materials, folding paper, repeating words/phrases/questions, playing certain songs/sounds repeatedly, seeking out nests/cocoons (like crawling into cupboards, or sleeping under the bed/in closets), enjoying high perches, seeking pressure on the body with weighted blankets or hugs, walking in circles, and more.

- Stims can have to do with any of the senses and are a way to comfort and calm and regulate our body and mind before we melt down or shut down.

- We can also self-regulate by having a safe “home” that we can return to, whether it’s a favorite story, song, or idea in our minds, or a favorite thing to watch, read, or hold.

- We may also demonstrate some common autistic postures, including keeping our arms high with wrists bent (sometimes affectionately called “T-Rex arms”), walking on our toes, sitting with legs in a W shape, curling up in chairs instead of sitting in them, etc.

- We often also stim when we’re happy! Many of us do a “happy flap” with our hands, rock/sway with joy, etc. for instance.

- Executive function challenges:

- Difficulty planning and following through on goals, daily chores, etc.

- Struggles with organization:

- we often love and even feel compelled to precisely organize finite spaces like a colored pencil box or bookshelf, and we are often very connected to objects and distressed if we can’t find them. In fact, we might really like to collect and keep lots of things from childhood and beyond, and feel they are like friends. (This adds a bit to the challenge of staying organized, but if we say something is important to us, it is, even if a neurotypical perspective wouldn’t consider it so)

- organizing more than a small box/area, however, can be very overwhelming for us to take on. We may like techniques like breaking tasks into small chunks, using lists, setting reminders, etc., but we also benefit from being allowed to make our own priorities for our spaces without judgment.

- Time management difficulty

- Inertia; difficulty getting started on things

- Distraction; getting easily sidetracked, lost in thoughts/imagination

- Task-switching difficulty. We benefit from having awareness of upcoming tasks/activities and fair warning about transitions. It often feels physically painful to be interrupted when we’re focused; we need time to switch gears, especially to be social.

- Challenges with focus. Moving our bodies, drawing/doodling, fidgeting/stimming can help us to focus on listening. (Please don’t ask us to sit still and look at you to focus, it’s stressful and counterproductive!) And conversely, listening to headphones can help us fight inertia and focus on manual tasks.

- Inflexible thinking: Preference for routine, difficulty with the unexpected, perfectionism, and rigidity about schedules, methods, rules, truthfulness, morality, and more.

- Unexpected changes to routine are very stressful, even if it’s for something fun. Autistic people will often feel truly shocked and thrown off balance by unexpected change. We may need time to come to terms with something like an impromptu decision to change a plan, add an outing, have a visitor, etc. And even when we have a previously scheduled event that is out of the ordinary, the entire day and even the night before can feel ruined by anticipation (we sometimes call it “waiting mode” or “anticipation stress”) for this event. (It helps if we can prepare — printing directions, google-mapping parking spots, writing a schedule, choosing clothing the night before, etc.)

- Taking pleasure in or having a need for order and control (executive function challenges can make it very difficult to maintain order broadly, but autistic people often seek order in more narrow ways). In children’s play, this can look like lining up and organizing toys. In adults, it can look like very careful planning, mapping, packing, list-making etc. for what may seem to others as non-stressful events or outings, focusing on maintaining order in a certain area of the house while the rest is entropic, as well as such things as researching the ends of stories before reading or watching them. (This is valid; please respect it. For some of us, the anxiety of not knowing would “ruin” a story much more than knowing the ending does.)

- Many of us do not like suspense or surprises. Especially surprise social events.

- Perfectionism… in small tasks and large, in interactions and projects, etc. We often hold ourselves to a very high standard and feel panic over perceived failures. This can couple with OCD or OCD-like tendencies. (I’m proofreading this post a lot and am still anxious about missing a mistake!)

- Difficulty with transitions between tasks, especially when not expected or without plenty of warning

- Hyperfocus to the point of tuning out the passage of time, our bodily needs, and other people. This can be wonderful and also frustrating for us.

- For some children, this hyperfocus plus other things can lead to something called “eloping”, wandering or even running away, generally in pursuit of something and with disregard to personal whereabouts/safety/other people.

- Hyperfixation (on specific ideas, activities, feelings, words, etc.).

- We may have a “special interest” — many autistic people, but not all of us, have one or a few passions in our lives that can be all-consuming and may be unusual. (This is not a problem – just a difference! Some autistic people have made huge advancements in certain fields because of their ability to focus on their passions, but even if we’re not advancing civilization in measurable or marketable ways, we’re fulfilled by these interests and we deserve respect.)

- Preference/need for the same foods, clothing, etc. day after day and repurchasing/stocking up on identical things. We may always order the same thing at a restaurant, due to social anxiety, choice paralysis, sensory needs, and more. We don’t need to be pressured to branch out unless were facing malnourishment etc.; ours is a valid way to be.

- Preference/need for the same timing, route, parking spot, etc. on walks/outings

- We often like to re-read books and re-watch movies/shows even to the point of memorization. It’s incredibly comforting to revisit the same imaginary spaces and narratives and characters.

- It may be hard for us to make choices that involve letting something go — even as regards brevity in our writing, as you may have noticed 🙂

- Strict rule-following and moral code for self and others

- Motor skills issues, either fine motor or gross motor or both; dyspraxia

- Some autistic people struggle with holding small objects, either using too much or not enough force

- Some of us struggle with general bodily awareness and tend to trip, stub toes, bump into things a lot etc.

- The idea of autistic people as “lacking empathy” is a myth. Autistic people often feel emotions very strongly. We also often have a high level of sensitivity to others’ emotions, even finding them overwhelming or painful. However, we do not always express emotions or comfort others in typical ways. Our feelings may be expressed through behavior seen by others as inappropriate (such as laughing or walking away at sad moments) or as unrelated, or our feelings may not show on our faces (flat affect) even as we’re overwhelmed or joyful etc. inside.

- The idea of autistic people lacking in imagination/creativity is also a myth. While it may seem that autistic children’s play is more about order than imagination, this varies tremendously from child to child, and does not in any way reflect whether or not we have a rich internal world of imagination. In fact, many autistic people are artists and writers (like me!).

- Co-occurring issues: we often have co-occurring diagnoses such as social anxiety, anxiety, depression, OCD, GI issues, immune issues/allergies, ADHD, rejection-sensitive dysphoria, etc.

- With our distinct ways of thinking come many benefits as well as challenges.

- We are generally very loyal and sincere.

- We bring unique perspectives; we can, for example, see and question harmful social and cultural norms (such as constraining gender expectations, racism, environmental irresponsibility, etc.) and may even work to challenge/dismantle them.

- We may be very detail-oriented, both in the context of being precise in our work and in the context of seeing beautiful things about the world that others may not notice.

- We are often very creative and can become unusually masterful at music, visual arts, etc.

- We are also often quite capable at understanding or creating complex systems.

- While we often struggle with executive dysfunction, we can be wonderfully focused on what we care about.

- Lots more

- Please don’t consider these abilities to be validating of our worth insofar as they give us economic potential or “make up for” our challenges. We are valid humans regardless of the unique talents we may or may not possess.

Terminology notes:

- Neurodiversity refers to the diversity of all neurology.

- A person who is not neurotypical is neurodivergent. That includes Autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and more.

- The word “spectrum” for Autism is commonly misused. It refers to the many categories of traits that together make us autistic, not a linear graph from “not autistic” to “very autistic”; neurotypical people are not “on the spectrum somewhere,” as some say — and autistic people are not ”on the spectrum” either.

- Autistic people generally* prefer to be called “autistic,” not “people with Autism” or the unnecessary and inaccurate euphemism “on the spectrum” — the second, “person first” terminology is often taught to teachers etc., but autistic people generally consider our neurotype to be part of our identity, not a disease or something we “have.” It isn’t separate from or detracting from our personhood, and trying to use euphemisms or “put the person first” is ableist and othering. *(As with everything, please defer to the preferences of the autistic person you’re speaking with/referring to).

- Functioning labels (“high functioning” and “low functioning”) are considered to be harmful by the autistic community because while we all have very different support needs, our uniqueness within the spectrum of Autism is not based on whether we are “very” or “only a little” autistic, but on much more complex factors. The terms are harmful because those called “low functioning” are often undervalued and not presumed competent; those called “high functioning” tend to be those who have worked to “mask” as neurotypical, but when we are denied needed accommodations because we are called “high functioning,” we often burn out. Rather than inquiring about whether someone is “high functioning or low functioning” it is best to inquire what their specific support needs are.

- The Asperger’s diagnosis was previously separate from Autism but is now folded back into Autism, and due to Hans Asperger’s cooperation with the Nazi regime, is a term that many people find offensive. (Read Neurotribes by Steve Silberman for the full history — it’s a great book and important to the Neurodiversity Movement). However, Aspergers and especially “Aspie” often remain an important part of the identity — especially for those who were given this diagnosis years ago. See above note about respecting an autistic individual’s preference.

—> This webcomic has a wonderful explanation of the spectrum, and how it isn’t about “more/less autistic” but about a wide range of traits, as well as how the “functioning labels” such as mild/severe Autism can be misleading and even harmful: https://the-art-of-autism.com/understanding-the-spectrum-a-comic-strip-explanation/

—> This article is very helpful, too: https://neuroclastic.com/its-a-spectrum-doesnt-mean-what-you-think/

What is masking?

“Masking” is a term used in the autistic community for when an autistic person learns through observation, trial and error, reading literature/watching TV, scripting, or through other means how to reduce their autistic-seeming behavior and appear more neurotypical. This can be a valuable tool for fitting into a society that privileges non-autistic behavior – it can help someone to advance in career, friendships, etc. Many autistic people have internal lists, rules, practice conversations, etc. that we employ on a daily basis in order to participate in social functions, as well as finding stims that are unobtrusive or even hidden.

However, long-term masking without a safe space to fully be oneself can also take a very serious toll and lead to meltdowns, exhaustion, and burn out. Just like everyone needs a balance between their private and public selves, autistic people should not be taught to always hide the parts of ourselves that are not convenient for a neurotypical context, but instead to value ourselves as we are. Due to the unaccepting nature of much of society, we may be glad for the opportunity to develop a toolbox to understand how to “fit in” and meet NT expectations when we wish to, but it should be our choice, and our acceptance should not be contingent on this!

Disabilities/Therapies/Accommodations:

Autism is a disability in 2 ways:

- Our traits and co-occurring conditions can be disabling in themselves

- To a large extent for many of us, Autism is disabling within the context of barriers in society. The lens of the “social model of disability” sees Autism as a disability primarily in terms of its location within a society that privileges neurotypical ways of speaking, moving, communicating, learning, etc. over autistic ways, thus refusing resources, acceptance, and accommodation to autistic people and pathologizing our tendencies.

—————

Being autistic in itself doesn’t require therapy.

There are therapies that seek to train us and shame us into hiding who we are, and these are wrong and often traumatic.

But there are some therapies that can really help autistic people to better understand, respond to, and advocate for our needs as well as — if we choose — to practice those things that will improve our lives within neurotypical society but may not be intuitive to us.

Occupational Therapy:

OT can be a great therapy if an autistic person is struggling with self-regulation. It really helps with self-awareness of needs and real lifelong tools without disrespecting the person (as long as they don’t use ABA – please read below about how ABA is harmful). Good OT does not try to condition away “unwanted behavior” but rather tries to help someone understand, safely respond to, and advocate for sensory and other needs. Not everything unusual or unexpected is a concern, and if it is, it can be addressed with support, not trying to change the person.

Speech Therapy:

Speech therapy can help with both receptive/expressive communication (including non-vocal communication; our communication preference may not be mouth words) and with social pragmatics (greetings, conversational back-and-forth, etc.)

ABA:

“Applied behavior analysis” is widely prescribed immediately upon a child’s diagnosis, but is based on problematic premises, including:

- the idea that any autistic child automatically needs to be “fixed” with hours of weekly therapy simply due to their not being neurotypical

- The idea that if an autistic child’s behavior can be changed through something akin to dog training or conversion therapy, then they will be less autistic and are being “cured” (as opposed to simply learning to mask personal needs and please authority figures, and learning to devalue their identity, making them more susceptible to future grooming, self-doubt, PTSD, etc.)

The overall consensus on ABA from those who value neurodiversity is that it interferes with children’s self-confidence, bodily autonomy, and self-respect about their way of being, and that the strict reward/punishment tactics with the child’s favorite things also destroy intrinsic motivation and trust. It basically trains them to perform (or mask) being neurotypical for the convenience of those around them, and at the cost of their ability to be emotionally and physically regulated and comfortable with their authentic self, with frightening long-term repercussions including PTSD and susceptibility to abuse. No matter how well-meaning the therapists are, ABA is inherently invalidating and anti-neurodiversity.

—————

—> There are also accommodations we can ask for at work and school etc.:

For instance, parents and schools might want to help a child with supports and accommodations such as:

- tools to help them maintain focus for class and independent work. *Do not make an autistic child try to sit still and look people in the eye for learning (sometimes called “whole-body listening”); that makes it much harder for us to pay attention, and it’s invalidating, ableist, and counterproductive to ask autistic people to conform in that way just for its own sake. Attention and eye contact are not the same thing for us. So instead, help kids find movements that help them with focus and don’t provide their own distractions. Autistic students might benefit from fidgets, a drawing pad, alternative seating options, and the option to take breaks from overstimulation, etc.

- tools for staying calm when facing change/transition or unwanted direction; plenty of notice before change

- guidance in peer interaction (such as understanding body boundaries, not walking away while someone talks to us, allowing others to choose what to play, etc.) while careful to respect and not broadly pathologize a child’s social and other preferences

- help managing and advocating for sensory/regulation needs in safe and appropriate ways. *Do NOT stop a child from “stimming.” When stims are shamed or punished or otherwise stopped, it leaves the person at risk for internalizing physical and emotional stress in unhealthy ways and can lead to meltdown and burnout. Instead, encourage children to stim in safe ways and, when possible without losing the stim’s regulating efficacy, less-disruptive ways.

- clear, explicit expectations/instructions, with written/visual supports when possible, and including those things considered “unwritten rules,” which are not obvious to us.

Since we never outgrow being autistic — though we often gain many skills along the way that aid us in adjusting to neurotypical society — we often need accommodations at work just as we do at school. Work accommodations will vary widely from individual to individual and job to job. Rather than try to list them here, I will say this: Please listen to and respect autistic voices.

Organizations/guides:

—> This is a great starting guide from ASAN, an autistic-run organization: https://autisticadvocacy.org/book/start-here/

—> Please avoid Autism Speaks; they are highly visible, but are run by non-autistic people trying to “cure” Autism (a problematic approach because (1) it’s a neurological difference, not a disease, (2) it’s a valid and valuable neurotype, (3) “cured” autistic people are generally those who have learned or been taught to hide their autistic traits to become more convenient to others, with long-term mental health repercussions). AS treat Autism as something that is purely an affliction on what would otherwise be a more valid/acceptable person, and promote therapies designed to banish autistic behaviors rather than help autistic people to be accepted as they are and to self-regulate and self-advocate. Many autistic people consider Autism Speaks a hate group — and the puzzle piece a hate symbol (the infinity symbol is preferred).

Online screening tests/checklists if you think you might be autistic (self-diagnosis is just as valid as medical diagnoses like mine. Access to knowledgeable diagnosticians, especially for adults with a lifetime of masking, is unfortunately subject to privilege and chance):

Autism tests

https://psychology-tools.com/test/autism-spectrum-quotient

https://www.aspietests.org/raads/

The CAT-Q

https://rdos.net/eng/Aspie-quiz.php

https://the-art-of-autism.com/females-and-aspergers-a-checklist/

Full text of Infographic above:

This April during Autism Acceptance Month, please remember:

—We don’t need to be “fixed” or “solved.” We have valid neurotypes that are part of human diversity. Listen to, support, and appreciate us instead.

—We are of every age, gender, race, etc. We have no specific “look.” We also have diverse talents, preferences, and needs. For more info, see: tinyurl.com/AutisticInfo

—Many autistic people consider the puzzle piece a hate symbol and Autism Speaks a hate group, with their focus on infantilizing & speaking over us and pathologizing, vilifying, & “curing” autism. We prefer the infinity symbol (gold for autism, rainbow for neurodiversity).

—Please refer to us as “autistic,” not “people with autism,” unless individuals tell you otherwise. Autism is integral to our identities, and we don’t need to be reminded that we’re people (neither should you!).

—Our disability comes in large part from society’s approach to us. Pressuring us to hide our ways of moving, communicating, thinking, and being in order to be convenient or appear neurotypical is traumatic. Let us stim, line things up, enjoy unique interests, skip “hello,” escape sensory overload, and whatever else we need to do to thrive as our neurodivergent selves.

*Please do not subject us to “therapies” like ABA that treat our authentic selves as a problem to be trained away. Autism does not require therapy, though some benefit from OT/speech that promote self-knowledge, self-regulation, self-advocacy, and skill with preferred communication methods.

—We don’t want “awareness” without acceptance and societal change.

Listen to #actuallyautistic voices

art and text by Carrie Schneider, 2022 @cs_auth_illus

One thought on “It’s Autism Acceptance Month! What does it mean to be autistic? ”